Surfaces and sequence graphs

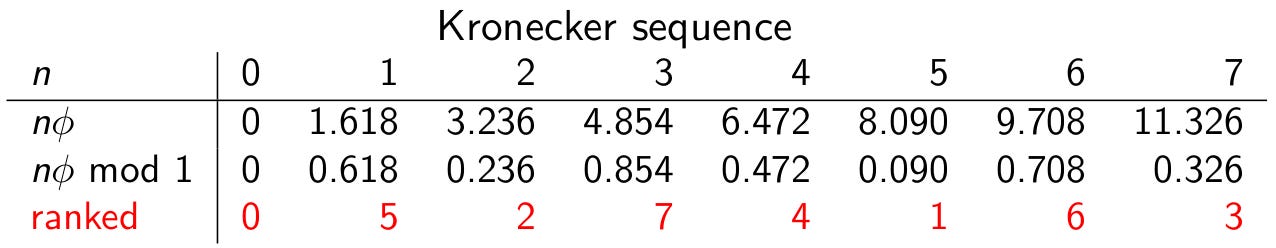

The golden ratio, φ=(1+√5)/2, is a famous example of an irrational number, which means that it cannot be expressed exactly as a ratio of two integers. The Kronecker sequence (nφ mod 1) is formed from the numbers (0φ, 1φ, 2φ, 3φ, …) ≈ (0, 1.618, 3.236, 4.854, …) by discarding the part of the number to the left of the decimal point to obtain (0, 0.618, 0.236, 0.854, …). The Kronecker sequence has no repeated entries precisely because the golden ratio is irrational.

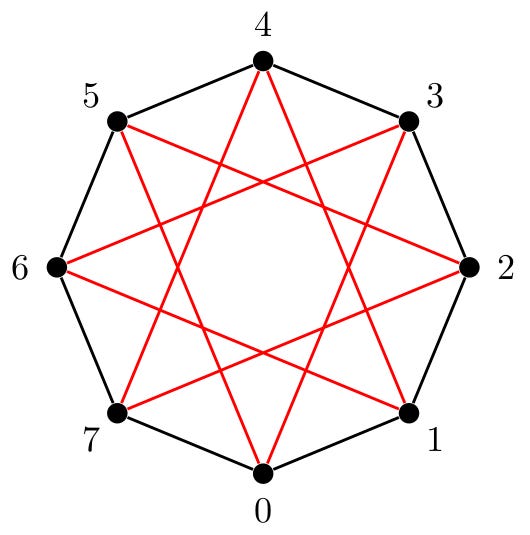

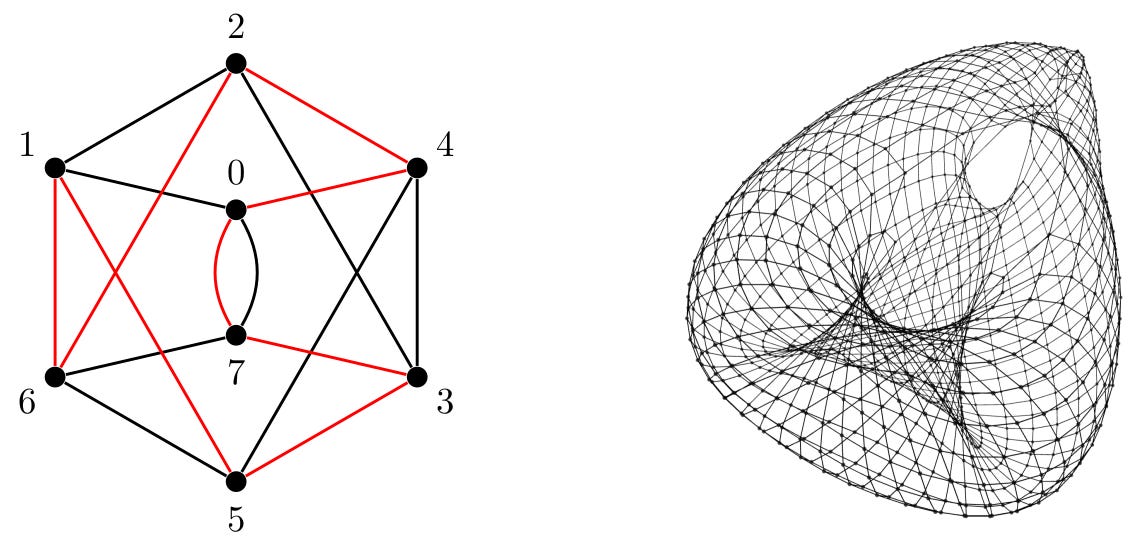

For each positive integer n, we can form a graph of vertices and edges called the Kronecker sequence graph. The example above shows the Kronecker sequence graph with n=8 vertices, labelled 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7. These vertices are connected in a cycle by black edges linking 0 to 1, 1 to 2, and so on, with 7 linked back to 0.

There is also a sequence of red edges that are determined by the first eight entries of the Kronecker sequence. If we rank the first eight entries of the sequence so that the smallest entry is ranked 0 and the largest entry is ranked 7, we obtain the sequence (0, 5, 2, 7, 4, 1, 6, 3). We use the red edges to trace this sequence on the graph, so that 0 is linked to 5, which is linked to 2, which is linked to 7, and so on, with the last entry 3 being linked back to 0.

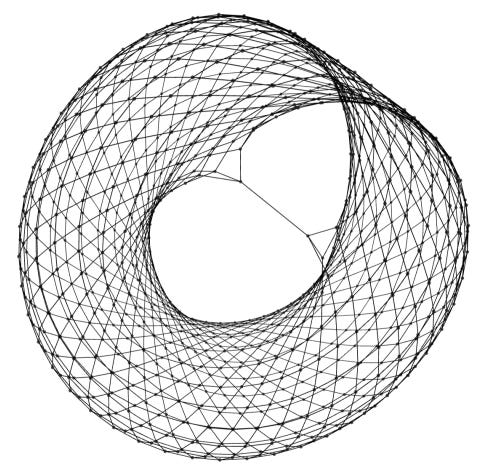

When n is much larger than 8, a geometric structure emerges from the Kronecker sequence graph, as shown above (with n=971) and also on the left of the top graphic. One of the results of the recent paper Obtaining the Chamanara Surface from the van der Corput sequence by Zawad Chowdhury, François Clément, and Max Horwitz is that these particular sequence graphs can be embedded in a torus. What this means is that it is possible to draw the graph, without crossings, on the surface of a torus, although in most cases it is necessary to remove an edge between n–1 and 0 in order for this to work.

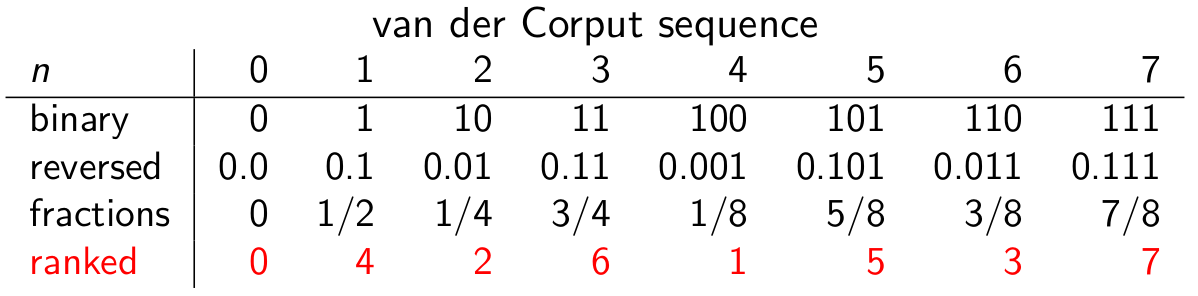

The main results of the paper by Chowdhury, Clément, and Horwitz concern a different sequence of numbers between 0 and 1 called the van der Corput sequence. To produce this sequence, we start with the sequence of natural numbers in binary: 0, 1, 10, 11, 100, 101, 110, 111, and so on. We then reverse the digits, and place the reversed digits after a binary point so as to make “decimals” but in base 2, which produces the sequence 0.0, 0.1, 0.01, 0.11, 0.001, 0.101, 0.011, 0.111, and so on.

These binary numbers represent the sequence of fractions (0, ½, ¼, ¾, ⅛, ⅝, ⅜, ⅞, …). As with the Kronecker sequence, we can rank the first eight terms of the sequence in order, which produces the sequence (0, 4, 2, 6, 1, 5, 3, 7). This gives rise to the red edges in the graph above, with the black edges following the cycle (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7). The right half of the picture shows the case n=1024, which resembles a surface of some kind. Larger values of n give rise to even more complicated surfaces, like the one on the right of the top graphic.

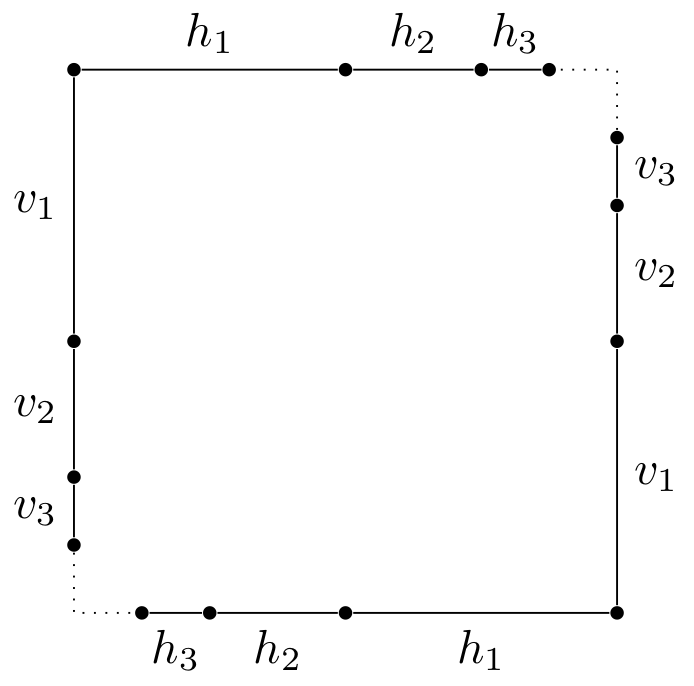

Chowdhury, Clément and Horwitz prove that the van der Corput sequence graph can be embedded into a particular geometric surface called the Chamanara surface, although in most cases it is necessary to delete an edge from n–1 to 0 to make this work. The Chamanara surface is constructed from the solid square shown below by identifying certain points on the boundary of the square with each other.

More precisely, we partition the boundary of the square into vertical segments vi and horizontal segments hi of length 2-i. Two vertical segments of the same length are then identified with each other, and the same goes for horizontal segments of the same length. For example, in the picture above, the left endpoint of h1 on the top edge is identified with the left endpoint of h1 on the bottom edge, and the top endpoint of v1 on the left edge is identified with the top endpoint of v1 on the right edge. The effect of this is that the top left corner of the square, the midpoint of the bottom edge, and the midpoint of the right edge are pinched together into the same point.

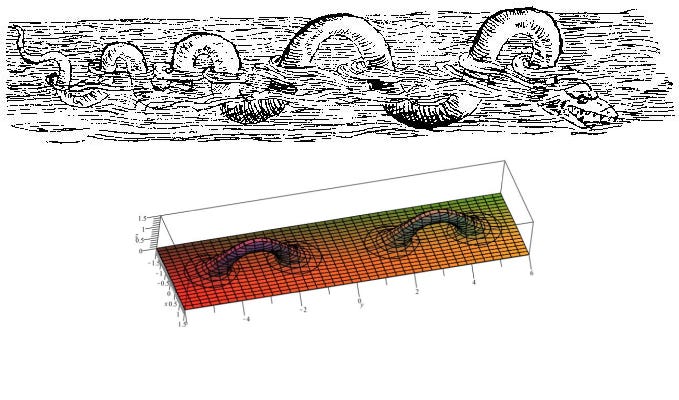

The Chamanara surface itself is an extremely complicated singular surface, which makes it hard to represent graphically, and the finite approximations to the surface depicted in the diagrams above can only be drawn in a comprehensible way because they avoid the worst of the singularities. The Chamanara surface is an example of what mathematicians call a Loch Ness monster surface because it has infinitely many handles.

Picture credits and relevant links

The Chamanara surface is named after Reza Chamanara, who described it in 2004.

The lead graphic comes from the 2021 paper Finding Structure in Sequences of Real Numbers via Graph Theory: a Problem List by Dana G. Korssjoen, Biyao Li, Stefan Steinerberger, Raghavendra Tripathi, and Ruimin Zhang. The authors discuss (mostly without proof) other aesthetically pleasing examples of surfaces that arise from sequence graphs.

The Loch Ness monster drawing comes from Nomenclator aquafilium animantium by Konrad Gesner, and the plot of the Loch Ness monster surface is by Boriaj. Both pictures appear on Wikipedia.

The tables are my own work. The other graphics come from the paper by Zawad Chowdhury, François Clément, and Max Horwitz.

Substack management by The Green Room.

Fascinating breakdown of how numerical sequences produce geometric structures. The progression from the n=8 case to n=971 really shows how complexity emerges from simple rules, kinda reminds me of how fractals work. I had no idea the van der Corput sequence could map onto something as wild as the Chamanara surface with infinit handles, the whole Loch Ness monster analogy is perfect.

I’m probably missing something obvious, but can’t reconcile these two statements:

> The Kronecker sequence has no repeated entries precisely because the golden ratio is irrational.

> These vertices are connected in a cycle by black edges linking 0 to 1, 1 to 2, and so on…

With no repeated entries, how does a cycle arise?