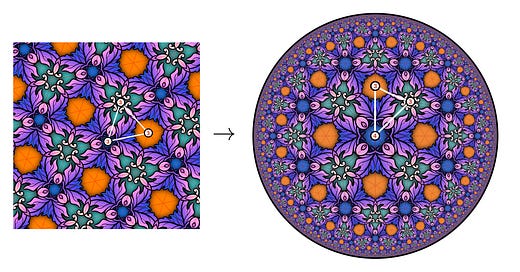

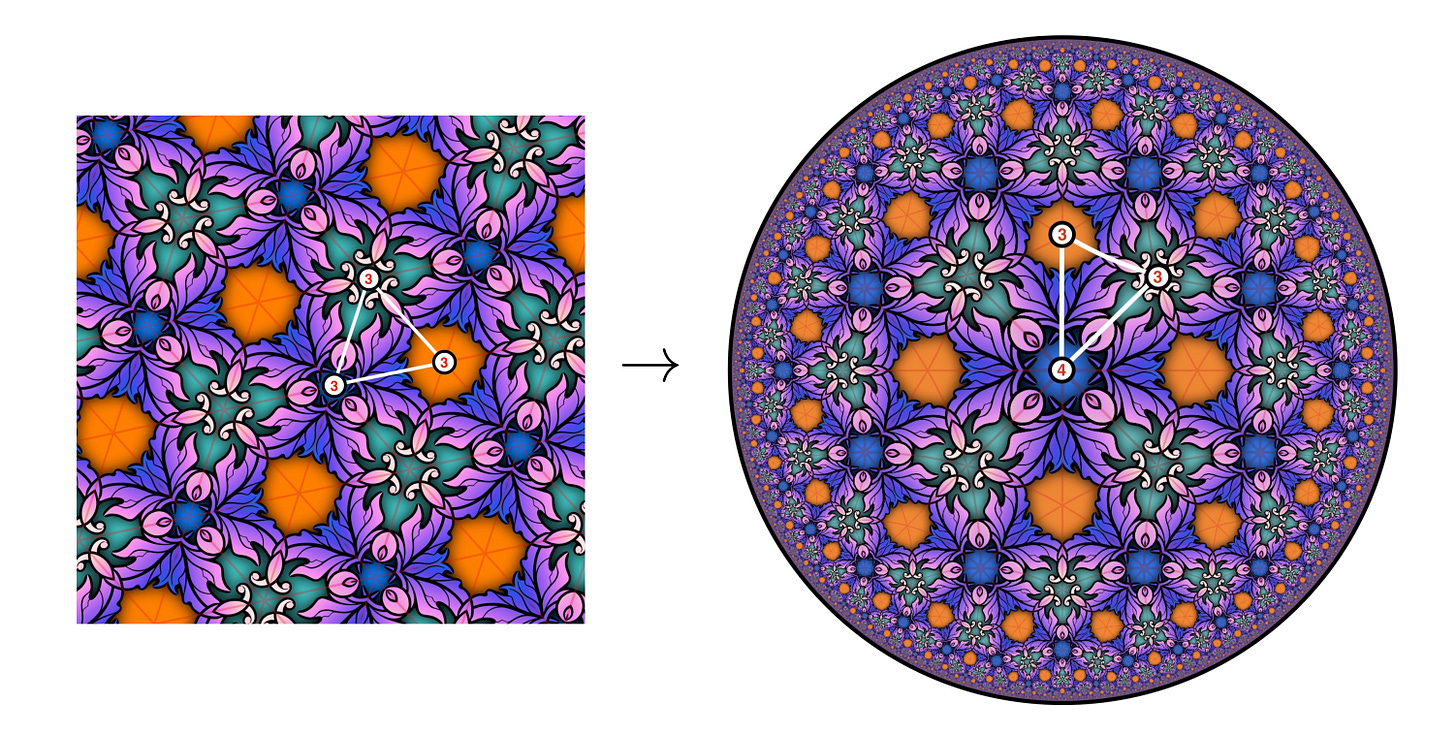

Given a repeating wallpaper pattern in the Euclidean plane, is there a good algorithm to turn it into a wallpaper pattern in the hyperbolic plane, as in the Circle Limit series of pictures by M.C. Escher? According to the recent paper The Smooth Power of the "Neandertal Method" by Aaron Montag, Tim Reinhardt, and Jürgen Richter-Gebert, the answer is “yes”. The authors show how to use the relatively simple “Neandertal method” to produce mathematically sound and aesthetically pleasing results, like the one in the picture above, without the need for time-intensive computations.

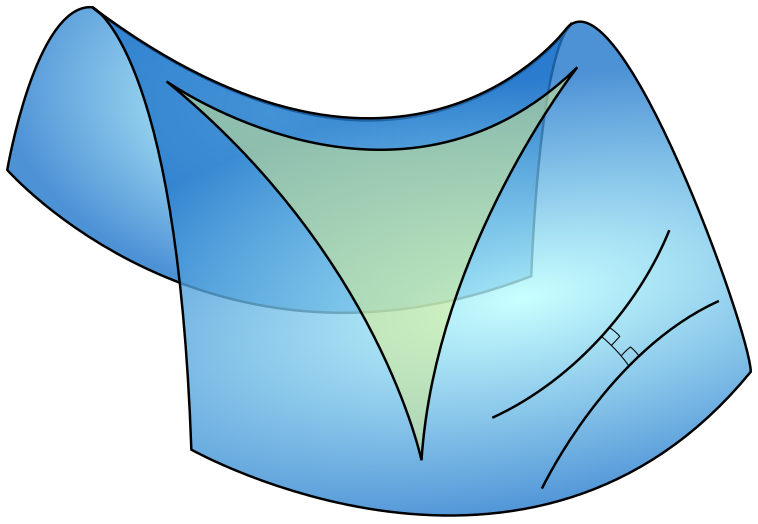

The hyperbolic plane is a negatively curved two-dimensional space, similar to the surface of a saddle. In the hyperbolic plane, the angles in a triangle add up to less than 180°. This is in contrast to the familiar Euclidean plane, which has zero curvature, and where the angles in a triangle always add up to 180°. For example, the triangle on the left of the main picture at the top has three angles of 60°, adding up to 180°, but the triangle on the right of the top picture has three angles of 60°, 60°, and 45°, which add up to only 165°.

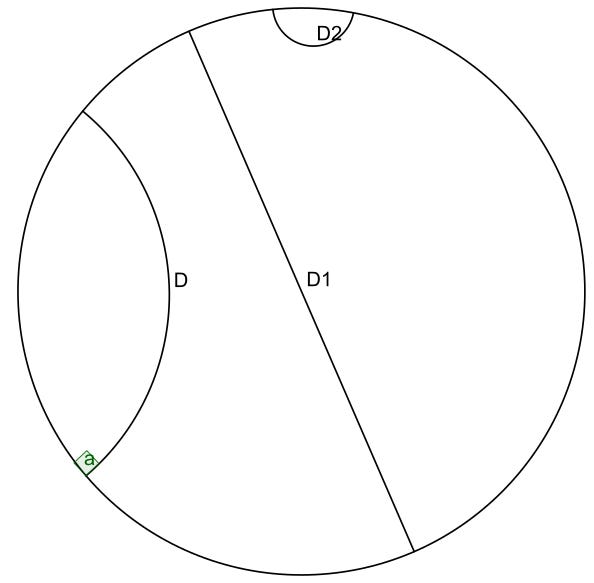

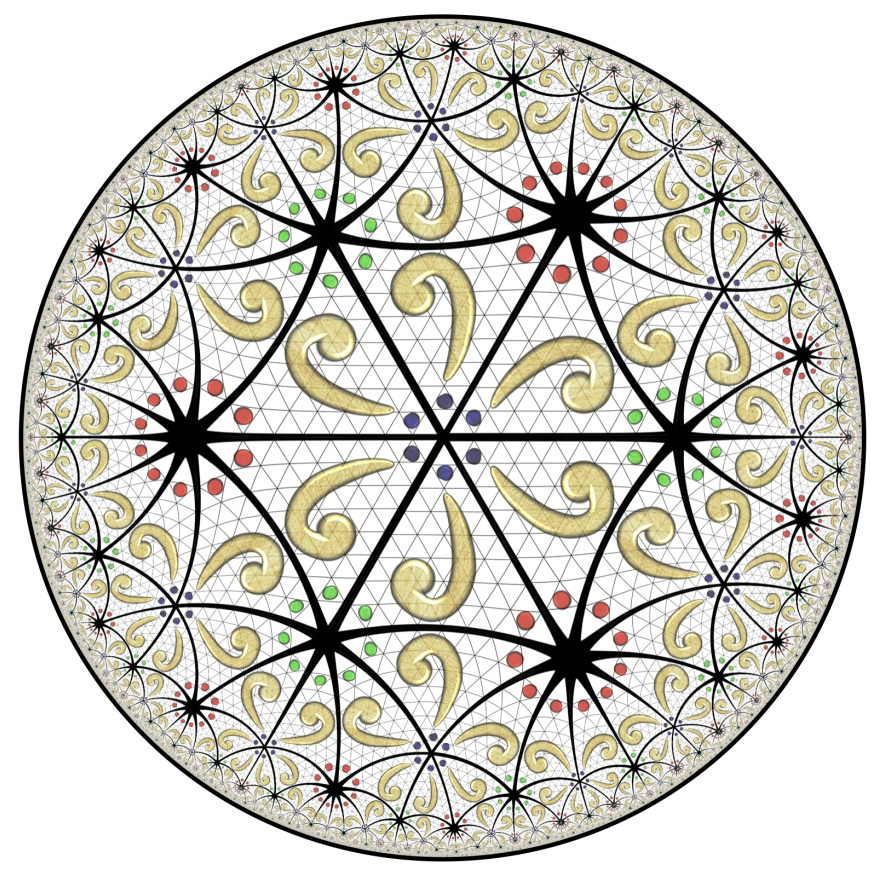

One useful model of the hyperbolic plane is the Poincaré disk model, which represents the entirety of the hyperbolic plane by the interior of a disk (i.e., not including the bounding circle). This model represents the straight lines of the hyperbolic plane either as diameters of the disk (like the line D1 above) or as arcs of circles that meet the bounding circle at right angles (like the lines D and D2 above). The three lines D, D1, and D2 are parallel, because they never intersect each other. The Poincaré disk model is a conformal model, which means that it represents angles between lines accurately.

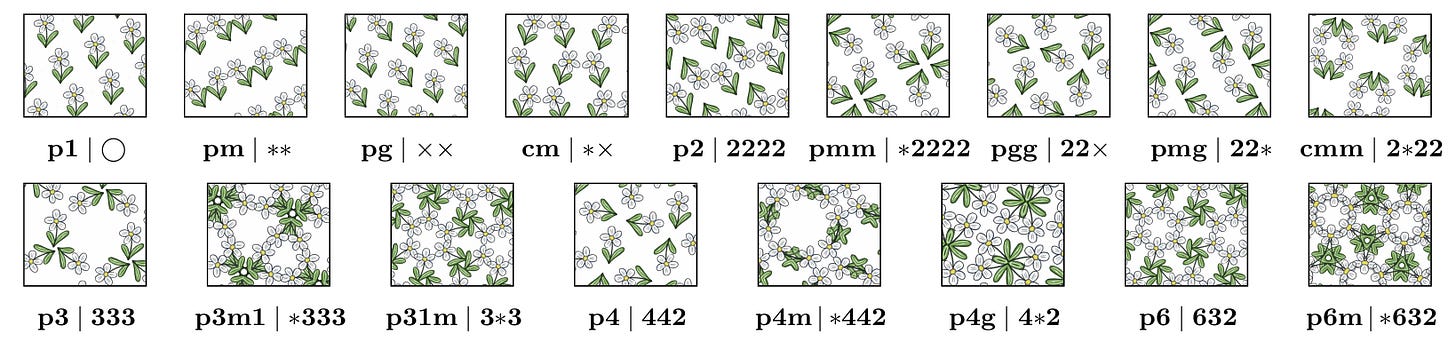

A well-known result in group theory is that, up to symmetry, there are exactly 17 types of repeating pattern in two dimensions, or in other words, that there are 17 different types of wallpaper designs. The symmetries involved in each one include rotations, reflections, and translations, as well as “glide reflections”, which are combinations of reflections and translations. The 17 symmetry types, and their notations, are shown above. Reflections and glide reflections are represented by the symbols ∗ and ✕, respectively. Numbers appearing to the right of a ∗ denote centers of rotation that lie on an axis of reflection.

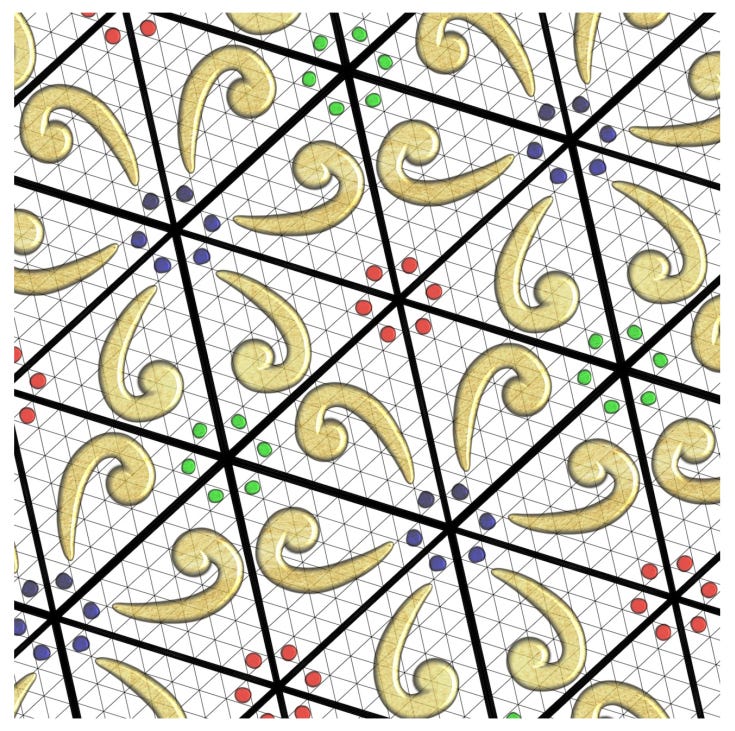

The Euclidean wallpaper design above has type ∗333. This means that the repeating motif has three centres of 3-fold rotational symmetry, and that each one lies on a line of reflectional symmetry. The hyperbolic wallpaper design below, which is based on the same motif, has type ∗543. It has three centres of rotational symmetry of orders 5, 4, and 3, located in the middle of the sets of red, green, and blue dots, respectively, and each one lies on a line of reflectional symmetry. The presence of fivefold rotational symmetry implies that it is impossible to have ∗543 wallpaper in the Euclidean plane. This is related to the fact that 2cos(360/n) is an integer if n=2, 3, 4, or 6, but not if n=5.

The paper describes an efficient computational method to construct a conformal mapping between the equilateral Euclidean triangle motif of the ∗333 wallpaper and the hyperbolic triangle motif of the ∗543 wallpaper. It is then possible to extend this mapping to the entire plane by applying symmetries. The method always works for 15 of the 17 wallpaper types, and it works in the remaining two types so long as the repeating motif is in the shape of a rectangle.

Picture credits and relevant links

The picture of the triangle on the saddle is in the public domain and appears on the Wikipedia page on hyperbolic geometry. Wikipedia also has a page about wallpaper groups.

The picture of the three lines in the Poincaré disk is by Jean-Christophe Benoist and appears on Wikipedia.

The other pictures come from the paper by Aaron Montag, Tim Reinhardt, and Jürgen Richter-Gebert. The third named author has an interactive web page where it is possible to play around with these hyperbolic tessellations.

Cool. Also, pretty!